“Sharks! Why’d it have to be sharks?”1 could have been Martin Brody’s complaint. When his wife asked what the technical term was for his fear of water, Brody replied with straight face, “Drowning.” How droll! It’s surprising then that Brody, a New York native, found his way to becoming Chief of Police of Amity Island (a fictional island) in Steven Spielberg’s first blockbuster, Jaws.

Jaws, in fact, was the first summer blockbuster in Hollywood history. It made a surprising $260 million. (That would be $1.58 billion today.) Filmed off Martha’s Vineyard, the movie production went over time and over budget. But test audiences loved the movie, so the studios advertised widely and the film was shown in 400 theaters.

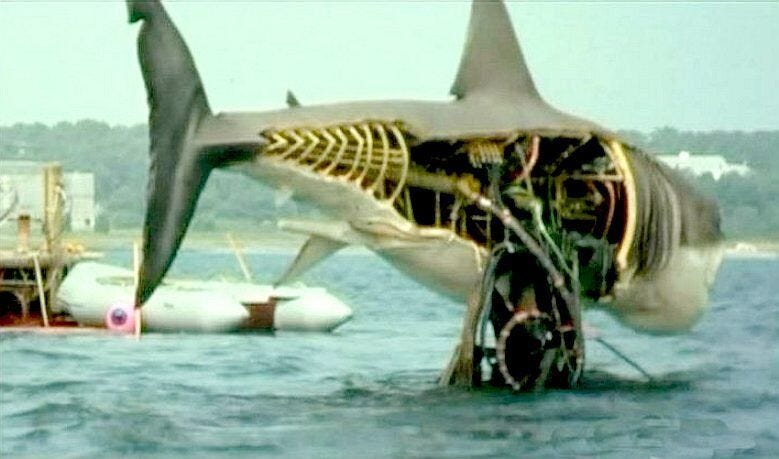

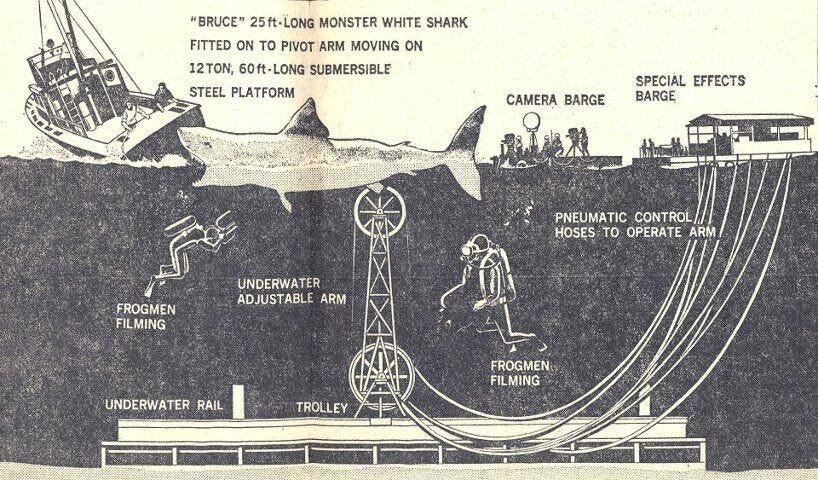

Eschewing filming in a tank, production was hampered by ‘Bruce’ the shark.

As you can imagine, in 1975 filming a movie in the ocean with an animatronic shark was no easy task.

The monster-sized 25-foot great white shark seen on film is an amalgamation of animatronic sharks and real-life footage. The crew shot the real-life shark footage off the coast of Australia. To give the illusion of the shark’s monster-size, a real 15 foot great white was filmed swimming around a miniature shark cage that housed a diminutive 4′ 11″ actor.

The animatronic sharks, on the other hand, were built to full 25-foot scale. Bruce, named jokingly by Spielberg after his lawyer, Bruce Ramer, was designed by production designer, Joe Alves, and constructed by Bob Mattey, who previously built the giant squid in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

Spielberg rejected the idea of using miniatures. He wanted the sharks to be full-size, and fully-operational animatronics that looked and moved like the real thing. In addition, he opted to film the sharks in the open sea (previous films shot ocean sequences in water tanks).2

The production used three sharks: one for moving right, another for moving left, and a third for moving forward.

Because filming ‘Bruce’ proved difficult, he actually sees very little screen time. Ironically, his little screen time amps up the tension and fear. In its way, the film plays on our fear of the unknown and unseen. The more you know, in many cases, the less anxiety. It’s like when you start a new job or take the first test of the semester or ride a rollercoaster for the first time. You don’t know what to expect so the anxiety is high. It’s part of the fun!

The casting was brilliant. Roy Scheider was hired based on his performance in the masterpiece, The French Connection. He’s brilliant here. He plays Martin Brody,3 husband and father of two boys, the single-minded police chief who is facing, not only his first summer on the island, but the shark threat. Richard Dreyfuss, who would go on to star in Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind, plays the oceanographer, Hooper, with great charm. In his way, Hooper is the heart of the film. Where Brody is quiet and steely, Hooper is emotive and exuberant. Their characters are balanced by the sulky Quint, who introduces himself in the film by famously scratching his nails on a chalkboard. He’s brilliantly portrayed by Robert Shaw, who’s drinking nearly derailed filming and caused problems between him and Dreyfuss.

Shaw’s drinking may have caused problems, but his acting was electrifying, especially his monologue about being on the USS Indianapolis during World War II.

This scene was written a couple of times, then given to Shaw who revised it. Shaw was drunk when they first filmed the scene. He begged Spielberg’s forgiveness and when they reshot it, they did it in one take. He delivers the monologue with a strange lyricism that pulls the audience in. Quint was on the Indianapolis, which delivered the atomic bomb to Tinian, part of the Northern Mariana Islands. After delivering their package, the Indianapolis went on its way to to meet the USS Idaho in the Leyte Gulf (the Philippines). On their way, just after midnight on 30 July (not in June as the movie has it), a Japanese torpedo hit the Indianapolis on its starboard side, igniting 3,500 gallons of aviation fuel. Another torpedo tore the Indianapolis into two. Of the 1,196 souls aboard, only 900 made it into the water. Of those, 316 survived. Estimates differ as to how many died by sharks, but it could have been up to 150 souls (not the implied 584 Quint mentions).4

Along with the death of the character of Alex Kinter, a twelve year old, who was killed by the shark when the beach should have been closed, Quint’s electrifying speech forms the moral core of the movie. The shark, a lifeless-looking, black eyed, perfect hunting machine (as Hooper says earlier in the film), needs to be hunted and killed. It terrorizes the community because it is soulless and hungry. The shark is emblematic of the fear instilled by the many soulless serial killers who preyed upon the American public in the 1970s. Ironically, only a New York cop, such as Brody, would understand the danger a hungry shark poses to a bucolic oceanside community.

It’s no wonder, then, that the lyrics of the famous ballad, “Mac the Knife,” compares murderer Macheath to a shark:

Oh, the shark, babe, has such teeth, dear

And it shows them pearly white

Just a jackknife has old MacHeath, babe

And he keeps it out of sightYou know when that shark bites with his teeth, babe

Scarlet billows start to spread

Fancy gloves, though, wears old Macheath, babe

So there's never, never a trace of red5

Here’s the great6 Bobby Darin singing it on the Ed Sullivan Show.

The shark’s terror is compounded by, or perhaps made more real and visceral by, John Williams’ brilliant score, for which he won the Academy Award.7 Rumor has it that Steven Spielberg laughed when Williams first told him about “the deep, quickening heartbeat.”8

On “Jaws,” Williams veered even farther from what Spielberg thought he wanted. The director had taken snatches from Williams’ avant-garde and often atonal score for Robert Altman’s “Images” and cut together a temp track. Williams had something totally different in mind, stripping the suspense down to just a few ominously accelerating notes. Would the film have succeeded without Williams’ score? It certainly wouldn’t have been the same movie, and from that moment forward, Spielberg made the composer a key member of his creative team, counting on a film to come alive during the scoring session. “It’s what I look forward to on every single movie,” he tells Bouzereau, who brings audiences inside several of those recordings.9

The music ratchets up the ‘scare-factor’ to terrorizing. The relentless duh-dum quickens the heart so that when the shark appears, nothing is left except for you to scream. It serves a kathartic purpose à la Aristotle. Kartharis for Aristotle, at least according to Jonathan Lear, is the safe release of pity and fear as one watches a tragedy wherein the audience member could be in the real life counterpart.10 Watching the shark terrorize Amity Island, one feels the pity and fear of the community in a safe environment: the movie theater. Although Jaws is not a tragedy, in Aristotle’s sense, thrillers like it serve a similar purpose. These types of stories release (as opposed to purge) our fears and dreads. We know that shark attacks are real, however rare they might be. Jaws allows us to release our normal, human fear of that terrorizing threat. In addition to giving us a great time watching a masterpiece!

Jaws turns 50 years old on 20 June 2025 (a week from this writing).

Daniel Rennie, “Revisiting Bruce, The Malfunctioning Animatronic Shark That Made ‘Jaws’ A Horror Classic,” Bold Entrance, 15 June 2020, https://boldentrance.com/remembering-bruce-the-malfunctioning-animatronic-shark-that-made-jaws-a-horror-classic/.

Not to be confused with Marcus Brody in Raiders!

Natasha Geiling and Meilan Solly, “The Sinking of the USS Indianapolis Triggered the Worst Shark Attack in History,” Smithsonian Magazine, 20 September 2024, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/sinking-uss-indianapolis-triggered-worst-shark-attack-history-25715092/.

Mack the Knife lyrics © Wb Music Corp., Bert Brecht, Kurt Weill Foundation For Music Inc., Estate Of Marc Blitzstein, Kurt Weill Foundation For Music Inc, Blitzstein Music Company.

Great singer, that is. As for his character, probably not so great.

His speech is short and sweet!

Peter Debruge, “‘Music by John Williams’ Review: Steven Spielberg and Friends Pay Rapturous Tribute to the Master Composer,” Variety, 23 October 2024, https://variety.com/2024/film/reviews/music-by-john-williams-review-steven-spielberg-1236189330/.

Debruge, “‘Music,’” emphasis mine.

Jonathan Leaer, “Katharsis,” Essays on Aristotle’s Poetics, ed. Amélie Oksenberg Rorty, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992), 315-340.